- Home

- Zhang Yueran

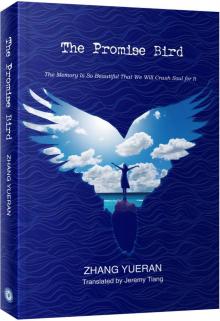

The Promise Bird Page 4

The Promise Bird Read online

Page 4

My heart calmed down over time. Other sounds stopped entering my consciousness; I was enveloped in a solitary slab of silence. The seashells were an opening to another world. The first time I heard a brief melody emerging from the shell in my hands, I let out a cry of joy. Perhaps at that very moment, Hua Hua paused in her work to listen. Would she understand my excitement? If not for the distance that had grown between us, I would surely have shared this with her.

It had been five years, and Chun Chi remained unable to find the secret she sought amongst the shells. She began going to sea more often. The life of an itinerant song-girl finally became too onerous, and she succumbed to old age.

She came back from one trip ill. For some time she stayed in bed, softly crooning, a seashell clasped in her hand from morning to dusk. I’d never heard her sing before, and only now realised what an outstanding performer she was. You could become lost in her songs. There were times when Hua Hua and I were compelled to stop what we were doing to listen in perfect stillness. The song was familiar, but I couldn’t remember where I’d heard it before. Perhaps she’d sung it to me in my cradle, or a previous life.

As I listened, I grew sad. It seemed to me that separation from Chun Chi was imminent. As a child I had dreaded her sea voyages, but now she was trapped in the house, I realised old age was more to be feared.

Hua Hua must have seen the tears flashing in my eyes. She sneered at my weakness. How I hated her at that moment. She had no way of understanding the meaning of Chun Chi’s song.

The servants brought the table of shells to Chun Chi’s bedside but she was already too weak to touch them without trembling. Her shivering fingers could only coax a few rushed sounds out of them.

I could sense her anxiety. There wasn’t much time left. Her temper was growing worse, and she frequently flung handfuls of shells to the ground.

The last batch of shells she had brought back would soon be used up, and still she hadn’t found what she was looking for. She became desperate to go back to sea, to join the crew in scooping shells from the ocean bed. But her body remained too weak for that, the great quantities of medicine she kept taking not seeming to make a difference.

It was time for me to take charge of the household. All this time, we had survived on the money Chun Chi earned singing on boats. She had never bothered about accumulating money, only seashells. Now the money was spent, and she would never be able to go to sea again, let alone sing. What would we do now?

I realised now how useless I had become, how Chun Chi had spoiled me. She had never asked anything of me, and I had grown up without accomplishments, content to let her support me. I was weak, pampered. All I had ever wanted was to follow Chun Chi, to dote on her. Perhaps my present predicament was retribution.

16

Chun Chi was unable to stop me going out to sea. There was nothing else she could do. The seashells were a drug she needed to stay alive. She became as weak as a maiden, and there was a sweetness in her new-found dependence. Finally, she surrendered.

We spoke for a long time, then grew silent. When she stirred slightly, I sensed it immediately. “Are you cold? I can warm your feet.”

I lowered her feet into warm water, the scarlet soles still delightfully bright. My fingers stroked them like seaweed, her feet icy as if all the heat in her body was leaving through them. I clasped them tightly, trying to rescue them with my own warmth.

As I dried her feet I looked up at her. She had no way of knowing how pure my gaze was, little different from the boy who wanted only to fall at her feet. I softly said, “Can you wait a little? I promise to bring you back what you’re looking for.”

I ran into Hua Hua as I left the room. She must have sensed the house thrumming with a new rhythm, but even in her fear she refused to look at me, and turned to leave. I called her name. Putting down the bucket of cooling water, I went up to her. We had been in this strange relationship for so long, I hadn’t looked at her closely either. She was now a grown woman, tall and slender where she had been chubby before. With her head lowered, she appeared to have a slight hump. Her body reeked of melancholy, but the same could be said of all of us living in that house. I felt a pang of regret for the round-faced girl holding her fat white cat, searching for the secret of the seashells. Her innocence and purity had been throttled by this house.

“I’m going out to sea,” I told her.

She bit her lip, but couldn’t stop it trembling.

“After I’ve gone, take good care of Chun Chi, do you hear me?” I knew she wouldn’t be happy to receive this instruction.

She finally found the courage to look at me. “I’d like to wash your feet one last time before you go.”

A room scented with sandalwood. A wooden bucket full of warm water. She lifted both my feet and gently splashed water onto my legs. I felt the soles of my feet growing lighter, as if floating on sunset clouds. In the still night, I grew weary, perhaps out of fear of the journey I was about to undertake. I rested my head against the back of my chair and shut my eyes. Warm drops of water speckled my shins. The clouds were dissolving into rain. Opening my eyes, I realised Hua Hua was crying, her head against my knees.

“Take me with you,” she said in a small voice.

Shaking my head, I pulled her to me and stroked her hair. My fingers had grown so sensitive from reading shells that I could feel sparks of desire beneath them, like fireflies rising from a still patch of grass. I reached towards them.

She finally collapsed into my embrace and begin crying in great gulps. Her voice distorted by tears, she said, “I know you like me, deep down, don’t you?”

I looked at her in confusion. Did I like her? I couldn’t answer.

“That’s enough for me. I feel lucky to have that,” she murmured.

She reclined against me with her eyes shut, smiling slightly. Lucky, she said. Lucky? Luck was an empty seat at the banquet of my life. I didn’t know what lucky looked like, had no idea what Hua Hua must be feeling now. But luck beckoned to me: worship Chun Chi, gather seashells, do these things and you’ll be on the road to lucky. But only approaching, never touching it.

I waned as Hua Hua waxed. She unfolded like a scroll, revealing a fairy landscape before me, mistily visible. I walked into it, unsure if it was Hua Hua herself attracting me or her heady aura of luck.

Now a grown man, I’d never been far from home, never had to consider supporting a family. This burden suddenly appearing around my neck paralysed me. Who could I speak to? I felt like a trapped animal seeking an escape. And at this moment, Hua Hua opened her arms to me.

I burrowed into her slight body, seeking warmth, hoping somehow to gain the courage to set off the next day. I’ve never felt much interest in girls’ bodies, making myself into an ascetic, walking a high and holy road above earthly things.

But her body was scalding hot, containing the warmth I needed. All my life I’d been so lonely, it was finally too much for me. Even now, at the moment of greatest intimacy, she remained hidden from me. Like the morning glory, her colour was pale and her scent faint. I held her tightly, afraid that as soon as I left her body this would all be forgotten.

She felt pain. A single tear ran down her cheek but she soon gained control, never letting go of me. She performed well, bringing me great pleasure and comfort. A second before we sprang apart, I felt myself unwilling to be separated from her body.

Exhausted, she slept leaning against me. I cleaned her body, treating her as tenderly as one of my seashells.

The next day, she didn’t see me off.

17

It was August when I left, following the same route Chun Chi had previously taken.

My first trip away from home. I was the same age as Chun Chi when she first left.

At that time, travel by sea made me unbearably excited. I searched for Chun Chi in each sheet of sea water we passed. I thought I saw her on a boat coming towards us.

Chun Chi left Lian Yan Island at the age of twenty-two. Her ship

crossed the Indian Ocean and followed the easternmost coast of China to Bo Hai Bay. On the long journey, she must surely have been seen kneeling on deck, softly weeping, or at other times singing a Malay lullaby to her tiny baby. She still had energy enough to pull out a deck of cards and tell everyone’s fortune. Her eyes were always brighter than the stars, and no one believed she could be blind. When she grew tired, she slept on the last row of chairs, not caring if it was day or night. She slept through many storms.

It was a long voyage, so long it felt as if all their memories were being tumbled onto the deck, like grains of salt, dried out by the cruel sun.

Many years later, I entered Chun Chi’s memories for the first time, an underground palace like the spiral of a conch. The events trapped here — her own, other people’s — swarmed like hungry ghosts at the scent of a warm body. Beneath many impassive faces lurk lost and broken souls.

They say memories want to be close to people. They lodge in our bodies, every recollection or graveside visit nourishing them. If unfortunate enough to be separated from their hosts, they dry out, desiccate, perish in the air. The lucky ones land in the ocean and take refuge in shells. They survive there, plump and lustrous, but in agony at being trapped in the deep, dark sea, uncertain when they’ll see sunlight again, when they’ll be reunited with human company.

This fragile woman awakened seashell memories with her delicate fingers. Drawn by the warmth of her body, they crept into her. A riot of bonfires, a cluster of dancing imps — Chun Chi was captured by the mesmerising flames, willing to give up her sight to prove her dedication.

And now, sitting amidst Chun Chi’s memories, I wait for past events to bury me. They arrive swiftly, a swarm of bees, a tidal wave of lava, crazed by the presence of a new flesh body. One after another, I pull them into my sleeves. They suck at me like leeches. I wait calmly, and when our blood has mingled, they are mine. I feel no fear, only acceptance.

Shuttle

1

One day in March, a man came to the refugee shelter on Lian Yan Island and took Chun Chi away with him.

He had been watching her from outside all that day, pressed close against the wall, his beard pasted by the heavy rain into stringy worms across his face. Finally, he tapped lightly on the window, at which Chun Chi jerked upright and ran to open the door for him. The moment he stepped inside, her world opened up like a music box.

For several days, she’d been aware of him watching her from the darkness outside. Some nights she saw his silhouette, solid as a fir tree amidst the fluid tropical vegetation. She couldn’t make out his face beneath its heavy beard, even his eyes only intermittently visible like twin moons through clouds. She felt no fear. There was something damp in his eyes, a warm summons.

He probably recognised her. Perhaps a former lover? After the tsunami took away her past, she lost even herself. Once, in the garden, he approached and grabbed her wrist in his giant hand. Flustered, she knocked over a wooden bucket and splashed him with dirty water, then fled, her dignity gone.

His heart must be in pieces, she thought: for his lover to be looking at him so blankly, as if at a stranger. Hiding from him, even. What pain he must feel. But he was determined, or perhaps their relationship ran too deep for him to give up easily. He no longer came close, but watched from a distance.

Free of memory, Chun Chi hibernated in an everlasting winter. It wasn’t till the man appeared and shattered the encasing ice that she stirred, pierced to wakefulness by his eyes, which made her realise for the first time that she was still a young woman. Her face flushed like a peach blossom aroused by the first breeze of spring. She wondered why the people around her didn’t notice she had become beautiful.

She began to take longer walks, always alone. This way, she could sense his presence, a constant ten paces behind her, the sound of his footsteps clear. He had strong legs; no matter how far they went he never slowed down. Walking before him, even when her breath came short and ragged, unimaginable happiness suffused her heart. The hill road was engraved in her memory: long, dense with jungle and bird cries, unspoilt. Silence all around, and then the thud of a coconut landing on the ground between them, rolling toward his feet. She didn’t dare look back, anxious he would conceal himself if she did. She had to pretend he wasn’t there. No one ever saw him accompany her on those walks. That carefree falling coconut was the sole witness.

One afternoon, as dark clouds hung low in the sky, Chun Chi realised she couldn’t hear the man’s footsteps on her way back from the beach. Abruptly alone, she panicked, emptiness enveloping her. Before a storm, flocks of crows always circled the hilltop where the refugees lived, their despairing cries infecting anyone who listened. She was abandoned.

Passing a pond, she paused to examine her reflection. She hadn’t changed at all: still the same cold fish, so ugly you could barely tell she was a woman. Had it all been in her mind? Perhaps there had never been a man’s gaze or footsteps. She had never been touched by spring. Her desperation to leave this place had caused her to fabricate this person, following her like a silent guardian angel.

Out of nowhere came a stuttering giggle, a tangled spool of hilarity like a silkworm’s skein. Without turning, Chun Chi knew the madwoman was behind her, hump-backed and silver-haired, staring, laughing.

The madwoman was a marvel. No one knew how she had survived all these years, alone in the world with nothing but insanity for company. Her whereabouts were difficult to predict — you might unexpectedly bump into her just about anywhere. Chun Chi had a soft spot for her. Despite her madness, she kept herself neat and tidy, and between manic episodes had the cool, sad poise of a rich man’s daughter. Chun Chi had run into her before, but never alone like this.

Already upset, Chun Chi’s frustration boiled over. Other people whispered that meeting the madwoman was a bad omen, especially after the tsunami — and sure enough, the strange man had vanished as soon as she showed up. She shouted and flapped her hands at the woman, who tottered backwards and then away on her bound feet. The surrounding woods suddenly seemed frighteningly quiet, traces of mad laughter echoing in the fronds of swaying tree ferns. No one was in sight. Chun Chi began running back to the shelter.

The stink of fish sauce pierced her nose: dinner time. The courtyard was full of women, filling the air with noises of contented chewing, like a particularly aggressive bird species, endlessly flapping but somehow unable to get off the ground. And yet they were at their calmest this time of day. At least you’d never get lonely in a place like this. Chun Chi heard Tsong Tsong call her name and went to sit beside her. As usual, she was with a gaggle of ladies of fading allure, listening to stories from their prime, of intricate dalliances with men.

Chun Chi choked down a mouthful of spicy soup, then looked up at the woman opposite her, all flying eyebrows and high colour as she recounted a shipboard encounter with a eunuch. A little chunk of rouge, badly applied, stood out on the oily surface of her skin. Even here, with no chance of a liaison, she still persisted in make-up; her rouge was probably retrieved from the waves, by now a paste of red mud.

Watching that bobbing patch of rouge made Chun Chi sad. She guessed it must have been a present from the woman’s lover, so brightly-coloured, almost a stamp of pride on her face. Hadn’t one of the other prostitutes talked about a client who licked her face clean of rouge, a glistening wet tongue dabbing slowly across her face — remembering this story, Chun Chi’s face flushed red.

Her already bad mood made worse by that stray scrap of make-up, Chun Chi abandoned her dinner, feigning illness. It was raining as she walked down the long corridor to the sleeping area. There was no one there yet, only the sound of rainwater leaking in. Chun Chi closed the door and flung herself on the bed, the only place in the wide world she could call her own. Curled up on the damp blanket, she began to cry in earnest, knowing she would have to stop before the women finished dinner.

Chun Chi was falling through a ravine with no sides, no bottom. The women surro

unding her were mostly seafaring song-girls. They weren’t bad people, but drifted languidly through life, trailing a miasma of decay. As soon as ships started coming in from China again, they’d get back onboard and continue with their old lives. Without the grand ships, without men to flirt with, without wine, without endless nights of music, they were like fish washed ashore by the tide, lacking even the energy to breathe.

But then she was as trapped as they were, or even more so. They at least could hope for a man to redeem them. What could she hope for?

Tsong Tsong was good to her. She owed her life to Tsong Tsong spotting her comatose body on the beach. Now it was a rope around her neck. Tsong Tsong once turned to her and said, laughing, “I saved your life. How will you thank me?”

Chun Chi’s heart sank as she replied, “How do you want me to thank you?”

Tsong Tsong pushed Chun Chi’s hair back and stroked her pale forehead. “I want you to stay with me forever.”

Her hand was ice-cold, a small white snake slithering across Chun Chi’s temples.

Tsong Tsong often asked, “When this is over, shall we try living on the ships?”

“I wouldn’t like that life. You aren’t free to be yourself. Always having to please other people and hide how you really feel.” Chun Chi spoke hesitantly. She knew that deep in her bones, Tsong Tsong was made of the same stuff as the song-girls.

“No, that’s real freedom. Surrounded by people who can’t see into your heart. They’re like waves. After some time on a boat, you forget it’s the ocean beneath your feet. All we’d care about is singing, drinking. We’d do as we please.”

In the face of such enthusiasm, Chun Chi could say nothing.

By the time the man with the big beard showed up, Chun Chi was struggling silently with the shackles of obligation Tsong Tsong was fastening around her. To look at her she seemed quiet, even docile, but that was just for show.

The Promise Bird

The Promise Bird