- Home

- Zhang Yueran

The Promise Bird Page 2

The Promise Bird Read online

Page 2

“I’ve always known that’s what happened,” I now said, my voice flat.

“And do you know why she did that?”

I shook my head.

“Just before that, I’d spoken to her about you. I said, ‘Xiao Xing is becoming more and more handsome. Such deep blue eyes, like a Persian. They say boys grow to be like their mothers. His mother must have been a great beauty.’ I meant nothing but good. She’d brought you up all these years with no idea what you looked like, and I pitied her. Yet her face changed to fury. When I asked her what was wrong, she laughed coldly and said — can you guess?”

“What did she say?”

“‘Xiao Xing’s mother was indeed a great beauty, but a short-lived one. If Xiao Xing truly resembles her, I’m afraid he isn’t much longer for this world.’ Such poisonous words! For all we know —” She looked steadily at me. “She was the one who caused your mother’s death.”

Her last words washed over me like demon fire. Auntie Lan’s face gleamed, and I no longer recognised her.

“I know,” I said slowly, and continued helping her pack. She was stealing some of our antiques, a Ding vase, a Zun goose-neck bottle, and these I carefully wrapped in her clothes. “I’ll summon a carriage for you. If you wait any longer, the roads will be too dark.”

Auntie Lan looked at me with disappointment. This cold youth, already beginning to sound like Chun Chi, who’d once loved her embraces, her soft bosom and milk-stained clothes. Auntie Lan began to weep, shouting that I didn’t know what was good for me, that my conscience had been eaten by dogs, that I was forgetting whose milk had nourished me. Who cooked and cleaned for me? Who waited at the schoolhouse when it rained?

I’d always known such a day would come. Through no fault of her own, she had never understood me. Her words would never change my mind, and served only to erode the affection between us. I’ve always been a man of few words, and prefer to go about my business in silence, untouched by what other people demand of me. I want to pass through the world like mist, unencumbered.

Auntie Lan finally stopped, exhausted from crying, her voice hoarse. She snatched her bundle and took a step towards the door, then suddenly turned back to say in a low voice, her mouth right against my ear, “What is it you hope to gain from her?”

She smiled craftily and strode away. I watched her go, trying to see her with clarity. Her tightly-bound little feet, her swaying breasts. It might not be long before I forgot what she looked like.

This vulgar wet-nurse. She knew that I preferred fish to pork; that I loved the rain, even though it made me catch cold; that my greatest ambition was to go to sea, to become a sailor. My smallest dislikes, my greatest dreams — she knew all of them. And yet she couldn’t see into my attachment to Chun Chi.

With each passing year, I discovered myself to be cool and detached, very like Chun Chi. The people around me didn’t inspire feelings of tenderness or warmth. They were a kind of weather: no matter how they changed, they wouldn’t affect me. Only Chun Chi was an exception to this.

Auntie Lan’s evil guess — that Chun Chi was responsible for my mother’s death — left a shadow at the bottom of my heart. As the memory of Auntie Lan faded, the idea became my own. If the days grew too dull or I missed Chun Chi too much, I only had to retrieve this thought — it had the same effect as biting my lip hard, the quickening scent of blood.

In my deepest soul, I secretly wished that Chun Chi really had killed my mother. This would be an unbreakable bond, our fates enmeshed, our lives inseparable.

I often dreamt that my true mother was standing at my door, tears like a fountain at night. I never opened the door, perhaps because to do so would be to betray Chun Chi. And so I never saw what my true mother looked like, but each time she appeared, the air filled with a distinctive floral scent.

5

After that, I stopped going to school when Chun Chi was at home, instead spending my days outside her door. Although she seldom left the house, she still attired herself with great care every morning, changing to evening dress when the sun went down — probably a habit acquired from her many years on the boat.

At times her door was ajar, and I could see her at her toilette. Needing no mirror, she stood at the window as she painted her brows, the first rays of sun just striking her face. She ran her fingers over her face, inch by inch until she found the corner of a brow, then dotted her brush at that point and carefully swept it across. Sometimes her fingers paused suddenly halfway across her skin, when they found a new wrinkle, which seemed an occasion of great sorrow.

When she was done, the windows and doors would be shut as she prepared to focus on her seashells.

At night, when the maid brought warm water, I dashed forward to take the wooden pail from her hands. This was the only way I could enter the bedroom. I knelt by Chun Chi, stirring the water till it was no longer scalding. Her feet were beautiful, firm and white as a young girl’s, but the soles were scarlet. Auntie Lan said this colour would never be washed off, it was far too deep.

The red hurt my eyes. I looked but did not dare to touch. It was a strange feeling, not fear but reverence. I wondered where such a pair of feet could have walked, touching my finger to a red whorl. It must have bled a lot. Did it still hurt? Suddenly I felt my finger was not smooth enough, my rough skin might damage her. In panic I looked up at her face, but she did not seem startled at my touch.

Those bright feet were like trout in the water, twisting with their own life, hinting at a mysterious past. Clutching them in both hands, I could feel them breathe. Gradually, my palms grew warm.

Time passed in this manner without me noticing, until she abruptly wrinkled her brow and said in a hard little voice, “The water’s cold.”

I lifted her feet from the pail and wrapped those wet fish in a towel. “I’ll change it,” I said, flustered.

“No need.” Her voice was icy.

Hurt, I left the room with the bucket.

Her room was full of wooden chests, each chest heaped with seashells, collected over many years. She worshipped them as other people do their ancestral tablets.

Her secret had something to do with these seashells. I wasn’t curious, but I worried about her, for the pain it caused her. I knew she was lonely, and perhaps needed someone to unburden herself to. But how would I find a way into her heart?

6

Chun Chi held the seashell, its markings seeming to tangle with the lines on her palm. She brought her mouth close and murmured to it, and it moaned softly in response, like an animal she had tamed.

I hid behind the screen, fascinated by the soft words, like clammy air. I felt like I had when, as a child, I’d climbed onto the window sill and plucked away the thick ivy until I saw a bright corner of sky. The shell’s response was like a nervous scatter of rain hitting the roof. The sound of flowing water was a river threading through my childhood, until I wanted to drown in it, become a slave to that sound.

As the shell grew warm, she stopped speaking and began tracing the surface of the shell, over and over, until it began spinning like a top. Her sensitive finger flicked against the whorls and grooves, harvesting something.

That afternoon, I woke up and slipped into the hall for a drink. Then I sneaked behind the screen with the gold filigree figures to spy on her.

She presided over a tableful of bright seashells, polished with a silk cloth till they glowed like coral, like a young girl’s cheeks. My eyes still clouded by sleep, I thought I saw highly-coloured skulls, vibrating gently in the wind from who-knows-where. Her normally dry eyes were moist, like lighthouses dappling an inky sea. Only at times like this could I see her pupils clearly, so beautiful no one would think they were blind.

Her fingers extended, she brushed their little foreheads. She never touched me like that. I turned and ran back to my room. Back in bed, I shut my eyes tightly, using a corner of the purple silk curtain around my bed to carefully dab away my tears.

Once, I broke a fig conch she�

��d left drying in the courtyard, badly damaging its crest and outer lip. As punishment, she ordered me to kneel while I mended it. The early summer sun made me feel faint as the pain in my knees slowly spread. The thick white glue stuck my fingers to one another and the conch. Finally I passed out, drifting gently to the ground. I was thirteen years old then, and already taller than Chun Chi.

When I came to, I was still in the middle of the courtyard, my fingers still glued around the shell. It was a basin brimming with sunbeams, full of seeds about to spring into life, ready to burrow into my skin and grow. While I was unconscious, it seemed to have changed my blood, or melted into it. We became a single living creature. I no longer hated it.

I stuck the shell together as best I could, filling in the missing portions with plaster and coating it with glossy white paint. It sat on the table and I stood beside it, not daring to move. The fig conch, repaired, gleamed like a little pagoda. Chun Chi reached out and fondled it. Suddenly, she asked, “Don’t you think this shell looks very like a human ear?”

I was overwhelmed. She had never sought my opinion before. “Yes, very like.”

“Have you ever placed a seashell by your mouth and spoken to it?”

“No.”

“Try. Whisper into it as you would an ear. It will answer.”

I did as she said, placing my lips close to the conch and speaking in a low tone. The shell had been polished so thoroughly it was almost transparent. My voice swelled inside it, creating little eddies of sound. I heard a returning whisper, the sound of the sea behind it, wave after wave coming towards me. The shell in my hand revolved like a planet, and I knew it was packed with stories. I looked up at Chun Chi and grinned with sheer happiness.

She smiled too, a sweet smile I had never seen on her before. It faded in an instant, but I stored it in my memory. No one can imagine how moved I was, as if a lifetime’s worth of good fortune had poured over me just then. I could not possess any more, I would never be so satisfied.

7

If it wasn’t for Master Zhong, I would never have known Chun Chi’s secret.

Master Zhong is the only visitor I remember us ever receiving. He always arrived on still and quiet evenings, like a shower of rain.

His job was to polish seashells for Chun Chi. He came to deliver the prepared shells, and take away a chest of new ones. Some of the shells still had remnants of little animals in them, and would rot if not properly cleaned. These needed to be soaked in cold water, then gently heated in a metal pot; while still hot, the flesh was winkled out with needles and small blades, the shells left to dry in the sun. This was the simplest part of the process. Many of them were infested with coral worms or kelp, and had to be scrubbed with a horsehair brush, any lingering specks chipped away with a little awl. Such fine work required both patience and great skill, and no one could have done it except Master Zhong.

Master Zhong came once a month, as regular as a lady’s time. I knew he was no common craftsman (if what he did counted as a craft). He had a razor-sharp gaze, meagre lips, and fingers as thin as twigs. His body was riddled with a foul, salty smell, as if he had just wandered in from the sea.

He was about the same age as Chun Chi, with clear, almost feminine features. Even at his age he had no facial hair or wrinkles, which made his face seem especially clean. He favoured long satin robes in dark green or black, finely made with embroidery on every fold. If I had seen him in the street, I would surely have taken him for some great personage, yet he abased himself before Chun Chi. Auntie Lan said (of course, this was just rumour) that Chun Chi’s father had been an important minister at the imperial court. I guessed that Master Zhong must have been a servant at their household — nothing else could explain why someone of his age would endure Chun Chi’s tantrums with such equanimity, why he was willing to undertake these dull tasks for her.

Master Zhong was very fond of me, although we hardly spoke. His joy at seeing me was palpable. He patted me, calling me with a suddenly hoarse voice, “Xiao Xing, Xiao Xing.”

The pity of it is, at the time, I misunderstood his affection for me as an extension of his feelings for Chun Chi, as if he would have loved a crow as long as it were under her roof. I stayed aloof, avoiding his hands, coldly informing him that Chun Chi was in her room or out at sea. He didn’t seem to mind the cold shoulder. Once, he brought me a present, a bunch of mandala flowers. “Put them in a vase by your bed. Maybe they’ll change your dreams,” he advised.

The flowers were crimson, drooping like bells, very fragrant. I had no vase, so I placed them in a teacup. When Chun Chi smelled the mandala, she became furious. Following the scent, she found them and shattered the cup on the ground.

After this incident, I hated Master Zhong in earnest for some time. He must have known Chun Chi disliked mandala flowers, and still gave me a bunch so I would anger her.

It was only many years later that I understood what he meant by “maybe they’ll change your dreams.”

Another time, I tried placing mandala flowers in a vase by my bed, like he said, but had no dreams at all.

8

Chun Chi never allowed Master Zhong into the house. He was forced to stand in the courtyard, like an animal that had blundered in by mistake. I heard him standing lonely by the trellis, coughing.

I remember very clearly the time he arrived on a wet summer day. It was raining hard enough to wash a person away. As always, Chun Chi refused him entry, and so he stood outside, utterly drenched. I couldn’t make out his face, but still remember vividly his pained, resigned appearance. As I watched him disappear into a foggy squall of rain, my resentment against him momentarily vanished. He must once have been a good-looking man, even if he was no longer young, and the beginnings of a hump made his dark green robes swell like a mottled tortoise shell, as if bowed under the burden of love he had carried all these years.

After he had gone, Chun Chi stayed in her room for several days. I stayed outside her door with my eyes shut, straining for the slightest movement from within.

When she finally came out, I was asleep against the wall opposite her door. “Xiao Xing,” she called. My eyes still shut, in the last instant before drifting free of my dream, I saw her walking towards me and reaching out to pat my head with infinite gentleness, as if I were one of her seashells.

Still half asleep, I stared at her. She had grown thin, her eye sockets dark. Her hair was brushed over her left shoulder, speckled with rainwater. (She must have been out in the garden — did she miss the man who had so recently left in silence?) Licking my lips, I realised how thirsty I was.

“Go eat your dinner.” Even spoken softly, this was an order.

She turned back to her room. I found my voice before she could close her door. “What can I do to make you happy?” As I clambered up from the floor, I felt my bones growing, faster than bamboo.

“Nothing.”

“I’d do anything for you.” My own voice startled me with its clarity. The sight of the forlorn man in the rain beneath his tortoise shell had left me shaken. These words, which had reverberated through all the years of my childhood, were finally spoken. I was a young man standing before his queen, sincerely honouring her as was her due, offering up the heart that had forgotten how to beat because of her.

She stood there, glimmers of light flickering across her blind eyes. The stolid youth had finally moved her.

But in the end, she shook her head, one hand groping until it found the edge of the door, burrowing back into her tightly closed shell.

9

On certain days, Master Zhong was accompanied by a little girl, his adopted daughter Hua Hua, a year or two younger than me. Wholesomely round-cheeked, she stood under the great locust tree by the outer door, looking for all the world like a fallen apple. She never once stepped inside the courtyard.

Once a month, I’d see Hua Hua beneath the tree, quietly playing by herself. After several years, the little girl blossomed into a young lady on the verge of beauty, like

one of the jade ornaments that hung from Master Zhong’s belt.

I will always remember the day she appeared at the courtyard entrance, pale and terrified. I knew nothing about her, only that she looked helpless.

She was thirteen years old. While she waited for Master Zhong, she often had with her a white long-haired Persian cat that mewed delicately. That day, the usually placid cat had struggled from her embrace and dashed inside, drawn by the briny smell of the seashells Chun Chi had left soaking in a stone trough.

Hua Hua stood in agitation, trying to see into the courtyard. A spring breeze shook the metal door knocker. She brightened suddenly, realising she finally had an unimpeachable reason to step through the forbidden doorway. She was short, her head barely brushing the door handle. Her hair was pulled back into a loose cloud without pin or ornament. Perhaps because she had been silent for so long, her voice was sandy. “My cat. White, long fur. Have you seen it?”

And so Hua Hua entered our courtyard. It took her a long time to reach the stone trough, she was so captivated by our plants: oleander, peony, dainty flowers loved by girls. When she looked into the water and saw all the shells, she was stunned into silence. From the dull purple of a floral shell to the orange starburst conch, from a clear sea-hare to the pagoda-shaped phoenix shell, these shells were gleaming gems in a crystal sheet. The locust tree shed tiny petals like stars. The outside of the trough had an carved pattern of children amongst lotus blossoms. Hua Hua carefully ran her hands over this, as if she wished to become a part of the engraving.

Reunited with her cat, she didn’t leave immediately. Indicating the trough, she asked, “Are all these yours?”

“No, my aunt’s,” I said with some hesitation. I’d never had to discuss Chun Chi with an outsider, and didn’t know what I should call her.

“Daddy mentions her a lot. She must be very pretty.”

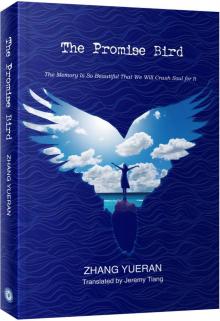

The Promise Bird

The Promise Bird